The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights uses some pretty blunt language in its recently published report to express its disapproval of the performance of the Home Office in what has come to be known as the Windrush Generation scandal.

Not enough was in place, it tells us, to “minimise the likelihood of such mistakes being made.” “Such mistakes”, it spells out, being the lack of awareness of the rights of the individuals concerned; ignoring evidence provided by family members, lawyers and MPs and letters from Government bodies like HMRC; wrongly placing the entire burden of proof on the people under suspicion when critical information could have been obtained from another department by Home Office officials; failure on the part of the officials to adequately satisfy themselves that they had a power to detain (and deport) individuals even when evidence on the case files strongly suggested that there was no lawful power to detain these individuals; and so on and so on.

All this amounts to ‘systems failure’ rather than a bundle of errors made by a bunch of inept Home Office officials. The question it brings to mind is exactly what system is judged to have failed in this instance. Is it the one that requires civil servants to check and double-check that their decisions comply in all respects with the requirements of the law? Or is it the bigger system, which sets out the grounds in which a group of people will be considered good immigrants, and therefore worthy of due process; or another type all together whose status as undesirables is so obvious they can be shunted off into the fast tracks that allow for detention and deportation?

Latest chapters

The Windrush migrants have had plenty of experience of the latter category, having been subjected to ‘colour bar’ discrimination in jobs and housing when they arrived in the 1950s and 60s and subsequent treatment that rarely raised their position and that of their children above that of second-class citizens of the UK. Mauled by the education system, winnowed out of the jobs market, and so many hauled up before the courts by criminal justice procedures, the sense of being part of a big family that appreciated them has been poorly developed across all these years.

The two cases featured in the Human Rights Committee report as exemplars of the bad treatment meted out to the Windrush immigrants, that of Paulette Wilson and Anthony Bryan, ought to be read as merely the latest chapters in the history of the racism to which black working class people have been subjected for decades. It is necessary to say black working class people because Ms Wilson and Mr Bryans’ status as, respectively, cook and painter/decorator, are as a significant part of the story as the blackness of their skin.

When it comes to immigration control, two great negatives feature as a fundamental part of the schema. The first is coming from a poor country, conceived as a place where people of colour are predominant among the general population. The second is being a wage-earner looking for work opportunities amongst the middle group of trades, requiring skills learnt on the job rather than the classroom. Being both black and a seeker of a position offering a living wage is part and parcel of any visa official’s basic definition of an undesirable immigrant.

“Turning the tap on and off”

It is important to hold this in mind as the options for immigration policy post-Brexit start appearing on the table. Liberal-types working out of the policy think-tanks encourage themselves with the knowledge that immigration will continue under whatever system is put in place, and if it can be honed down to those who the focus groups tell us are acceptable – skilled professionals and international students – then all might be well. But by accepting this as a defensible position they are acceding to the prejudice that remains entrenched against non-professional, working class migrants.

Labour MP Caroline Flint, apparently ignorant of the fact that she was speaking in the midst of a scandal about the treatment of Windrush immigrants, offered up a vision of what her ideal post-Brexit immigration policy would look like during a debate in the Commons in mid-June. She set out a yearning for an immigration system in which “… we can turn the tap on and off, when we choose.”

Yet when we treat people as a flow of commodities which we can be turned on and off, then we assuredly create the very situation which Flint’s parliamentary colleagues excoriated just weeks previously in a memorable debate in the same Commons. Years spent as members of communities, as workers in pursuit of a decent living, as people raising families and doing their best to fit in, count for little or nothing when it comes to deciding when the tap has to be turned off.

Getting beyond Windrush

The Parliamentary Human Rights Committee was right to point to systems failure rather than a mere cascade of mistakes in its judgment on the Windrush affair. But it is a failure that has its root in the deep contempt that the middle-class Britain made up of people with property-portfolios and assets yielding a stream of rent-income has for those who get by as best they can by selling their labour to whoever will buy it by the week, day or hour.

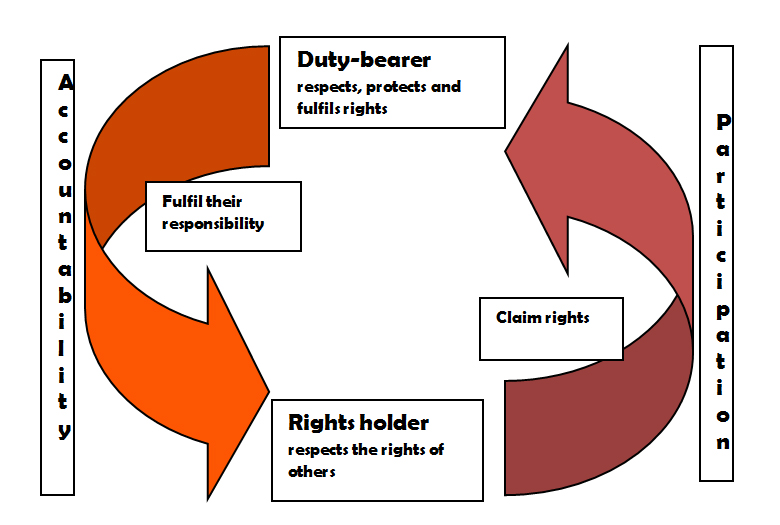

Getting beyond the Windrush scandal will mean forming an entirely different perspective on those who come from any part of the world looking for the chance to earning a living denied to them in their own countries. It should not be that only the passage of forty or more years of living the life of working class Britain wins grudging admission that you have ‘contributed’ and therefore accumulated at least a few rights. Rights ought to be the basis of immigration policies, available equally to the cooks and painter/decorators of this world as anyone from the more esteemed professions.